Guns & Roses: Chicago's Bloody Valentines

Nelson Algren likened loving Chicago to "loving a woman with a broken nose."

But Valentine's Day in Chicago has gone far beyond loving imperfect women. It's oozed into the much less poetic territory of loving insane women, men with "the devil in them," as Chicago's matchless serial killer H.H. Holmes pegged himself, and loving (in that incomprehensible way of the doomed together) our world class gangland warriors, among them the ever-undisputed king of crime, Al Capone--without whom Chicago would be nothing more exciting than a particularly lovely and somewhat edgy example of what happens when people rally after a tragedy (see entry for the Great Chicago Fire).

As a ghostlorist, I would say that Chicago defines itself--right under the tendency to say "To hell with what just happened"--in her passion regarding both love and hate, devotion and disdain. We like our polar emotions. Every February, while the rest of the world is buying flowers, chocolate and diamonds, Chicago is getting ready to mark the most infamous Valentine's Day in history: the blustery day in February of 1929 when Chicago became the immovable center of one of the most controversial eras in American memory. "Prohibition" brought fame to Chicago that would last, seemingly, to eternity. As in many other cities throughout the United States, Chicago remained very wet throughout the decade. Higher class operations were known as "speakeasies" while dram shops were called "blind pigs," where customers would pay to see live animals and drink alcohol behind unmarked doors.

Capone vs. Moran: A Deadly Rivalry

Most not familiar with Chicago history see Italian-American mob boss Al Capone as the unchallenged king of Chicago during this time; but in fact, throughout the decade, Al Capone went neck and neck each day with his rival, George "Bugs" Moran--head of the north side Irish mob in Chicago. The two of them fought for control of turf in the "Beer Wars," much as the drug lords of Chicago fight today.

Their battles hatched some of the most lasting ghost stories in Chicago history, including stories about the hotels where Capone held court, fables about the sites of infamous shootouts, and the treacherous site of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, where seven of Moran's men were lined up on that bitter morning and gunned down against the rear wall of a now-demolished garage. Even today, residents who live in the buildings adjoining this now vacant lot tell a curious tale: after a fresh snowfall in Chicago, you can sometimes see the outline of seven bodies in the snow, right where the rear north wall of the garage once stood.

In Chicago, coupled with these stories are the tales of some of the most ill-fated loves in American history. Consider the love story of Adolph and Luisa Luetgert, (the "Sausage King and Queen of Chicago") which began as most immigrant love stories did on Chicago's North Side, but which ended with neighborhood children singing rhymes about Luisa being made into sausage by her husband after she mysteriously vanished, never to be seen again. It is said that Louisa's ghost still roams the vicinity of Diversey Parkway and Hermitage, where the old factory now houses loft condominiums.

Then there's the story of the Woman in Red, a beautiful young woman who attended the opening night party at the Drake Hotel with her fiance on New Years' Eve 1920. Before the clock struck midnight, she discovered her love in the arms of another girl and hurled herself off the hotel roof. She is said to still be seen in wandering the halls, the skirts of her rosy gown swooshing around the corners, her sobbing still audible to startled guests.

Then there is the story of Herman Schuenemann, the captain of the "Christmas Tree Ship," who sailed the Rouse Simmons to Michigan on his annual journey to bring Christmas trees back to Chicago--who was never seen again. It is said that the scent of pine needles can still be smelled at his wife's gravesite in Chicago's Acacia Park Cemetery, nearly a hundred years after the ship was lost.

And there is eternal tale of "Resurrection Mary," arguably Chicago's most famous ghost, who died on a lonely Chicago road in the wee hours of the morning--only to haunt the city's memory forever. As Chicago's most long-standing dance partner, Mary has captured the imagination of generations hoping to help her find her way home at last.

Still, there is no doubt that it is the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre that continues to make Chicago’s Valentine’s Day celebrations-if that is the right word—utterly unique in the world . . . and the site where it happened one of the city’s most enduringly haunted.

Crime buffs eager for a tour of Chicago's gangland attractions are often disappointed by the city's lack of preserved locations.

Many of the most notorious sites in the history of Chicago organized crime no longer exist, leaving no evidence but memories of the madness with which they were connected. Gone, for example, is Big Jim Colosimo's restaurant at 2128 South Wabash Avenue where the owner prided himself both on his smoothly-run empire of vice and the "1 million, 500,000 yards of Spaghetti Always on Hand." Also gone is Sharbaro and Co. Mortuary, 708 N. Wells Street, which hosted two of the biggest funerals in gangland history: one in November 1924, when Dion O'Banion was carried out the front door in a $10,000 casket; the other in October 1926, after Hymie Weiss was gunned down on the sidewalk across from Holy Name Cathedral while attempting to avenge O'Banion's death.

The Four Deuces Saloon, now a vacant lot at 2222 S. Wabash, long ago welcomed Al Brown from Brooklyn to his first Chicago job as the bouncer who would become known in infamy as Al Capone. Later, the Lexington Hotel at 2135 S. Michigan Avenue would serve as the seat of Capone's crime kingdom. Alas, that palace, along with Capone's own fifth floor suite, has also been demolished.

For organized crime enthusiasts, however, more missed than any of these is the warehouse which stood at 2122 N. Clark Street, where on Valentine's Day 1929, one of the most gruesome multiple homicides in gangland history was committed. The building nearly eluded description: a one-story red brick structure, 60 feet wide and I 20 feet long, tucked between two four-story buildings that in 1929 somewhat towered over the S-M-C Cartage Company garage between them. On the morning of February 14, a sordid group was gathered inside in retreat from a typical snowy Chicago morning. Ex-safecraker Johnny May, having been hired as an auto mechanic by the notorious gangleader, George "Bugs" Moran, was stretched out under a truck fixing a wheel. Living out of a slipshod apartment, May was grateful for the 50 bucks a week he got from Moran to support his wife, six children, and a dog named Highball, who happened to be at work with him that morning, tied to the axle of the truck.

Huddled around a percolating coffee pot on an electric hot plate, shivering in their overcoats and hats, were another half-dozen assorted characters, including Frank and Pete Gusenberg, who were, per Moran's orders, awaiting a truck-full of hijacked whiskey from Detroit. Moran himself was late for the I 0:30 a.m. rendezvous. It was a I ittle after the appointed time when he finally ventured out into the 15 below zero cold with Ted Newberry, a gambling concessionaire, headed towards the garage. The Gusenbergs were antsy, anxious to get started on their own part of the scheme, driving two empty trucks back to Detroit to meet a haul of smuggled Canadian whiskey. Their companions, however, were carefree, having been summoned by Moran merely to help unload the trucks when they arrived. Among the harder hearts-Moran's brother-in• law, James Clark; financial whiz, Adam Heyer; and newcomer Al Weinshank-was Reinhardt Schwimmer, a wanna-be of sorts and a young optometrist who had glommed onto Moran after befriending the gangleader at their mutual home, the Parkway Hotel. After that meeting, Schwimmer frequented the North Side warehouse hangout for the thrill of illicit companionship.

Inside the Fatal Morning

None of the group suspected that what looked like a police car had pulled up outside the building -- or knew that Moran, spotting the car upon his approach, had hightailed it to a coffee shop on the corner to wait out what seemed an imminent raid. While Moran's men whiled away the time under the light of a single naked bulb, four men emerged from the car outside, two in police uniforms and two in civilian clothes. The landlady of a neighboring rooming house watched as the men entered the building, then gasped at the clattering explosion of sound that followed a few moments later.

Soon after, four figures emerged, two marched at gunpoint by the two men in uniform, amid the clamor of a barking dog. After the car pulled away from the curb and headed down Clark Street, the neighbor, concerned over of the still-howling dog, sent a man in to check on the animal. He remained inside only a few moments before reappearing to report on the scene inside.

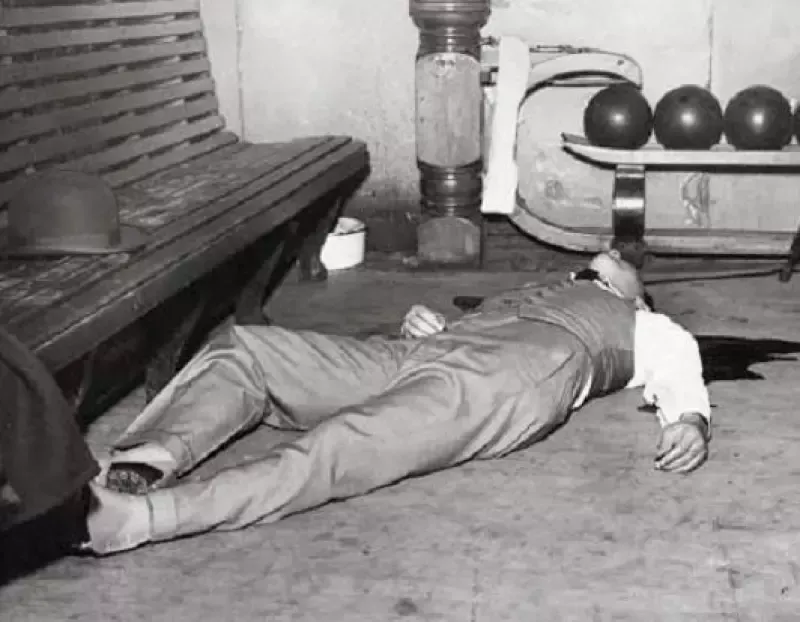

Moran's men had been lined up against the rear wall of the garage and sprayed by machine guns in careful swoops of fire which targeted first their heads, then their chests, and finally their guts. Despite the shower of death, May and Clark had lived, but with their faces nearly blown off by close-range shotgun blasts. Remarkably, Frank Gusenberg had also survived. When Detective Sweeney arrived at the massacre scene, he recognized the face of his boyhood friend on the body of the bullet-riddled Gusenberg. With 14 bullets in his body, Frank had crawled 20 feet from the blood-soaked rear wall, from where he was taken to Alexian Brothers Hospital. There, upon Gusenberg's revival, Sweeney would repeat the question he'd first posed in the garage: "Frank, in God's name what happened? Who shot you?" only to receive Gusenberg's famously hard-boiled response, "Nobody shot me." Still urged by Sweeney to reveal the killers, Gusenberg instead spat out his last words: "I ain't no copper."

But while the law was temporarily baffled as to the source of such brutality, Bugs Moran immediately named its orchestrator. Upon hearing the news of the gruesome deed, he flatly proclaimed, "Only Capone kills like that."

In fact, Al Capone was at that moment in Florida, playing host at his lavish Miami resort. When questioned by one of his guests about his involvement in the Chicago tragedy, Capone curiously but firmly responded that "the only man who kills like that is Bugs Moran."

Indeed, though there was (and is) little doubt in anyone's mind that it was Capone, not Moran, who had been the brains behind the bloodbath, the crime remains officially unsolved to this day. Still, while some later stories differed on the names of the gunmen, the core team was almost certainly comprised of Capone's standard slate of executioners, led by "Machine Gun" Jack McGurn (who, incidentally, got his nickname from being a stellar boxer, not assassin). McGurn went on to elude conviction because of the unwavering coolness of his girlfriend, Louise Rolfe, his "blonde alibi" who convinced police that the two were together during the time of the Massacre. Several years later, also on Valentine's Day, McGurn--who during the Great Depression had lost everything but the fancy clothes his Prohibition dollars had bought him-- was found shot to death in a north side bowling alley, an insulting "Valentine" note dropped at his side. Revenge had been served very cold indeed.

The Haunted Legacy

In 1945, the front of the S-M-C garage was turned into an antique shop by a couple oblivious to the property's infamy. Unfortunately, their doorway was visited more often by crime buffs than by antiquers, the former of which came to the garage in droves from all over the world and eventually forced the disgusted couple to abandon their venture. Later, in the late 1960s, the building was demolished and the 417 remmaing rear wall bricks (which had not been stolen by souvenir hunters) hauled away by George Patey, a Canadian businessman who first built them into a wall of his nightclub. Today the wall stands in the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, though many of the so-called "Chicago bricks" are still circulating. According to rumors, however, anyone who purchased one of the S-M-C bricks was besieged by bad luck, in the form of illness, financial or family ruin, or any of a variety of other maladies. The very structure seemed to have been infused with the powerful negativity of that Valentine's Day.

As did the site.

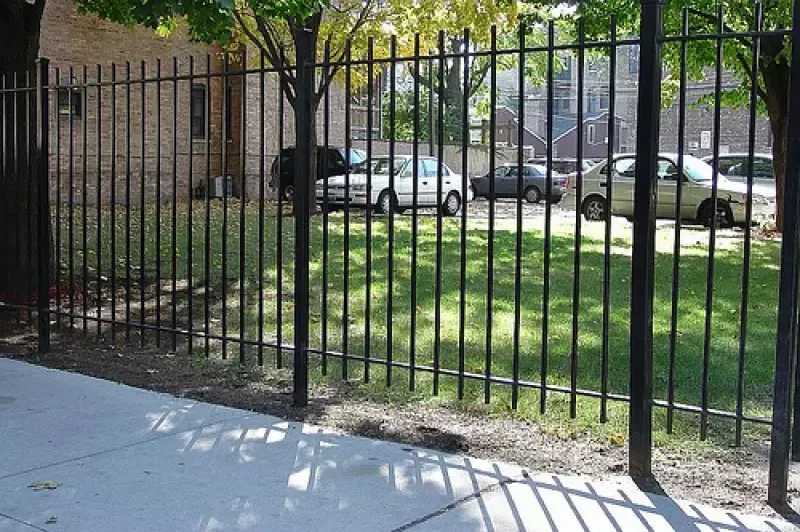

Five trees dot the otherwise nondescript space, the middle one marking the spot where the rear wall once stood. To this day, an occasional stroller along Clark Street will report hearing violent screams ringing off the fenced-off lot once occupied by the garage that is now part of a nursing home's side lawn and parking lot. Moreover, those walking dogs are often puzzled by their pets' curious reaction to this stretch of sidewalk, as their animals either growl or bark furiously at the apparent nothingness or whimper as they crouch away from the iron fence. Perhaps dogs, known to be more psychically sensitive than most of their masters, are reacting to something unknown to their human companions, a massive surge of energy produced and sustained at the site by the impact of the massacre; a vision of Highball, forever snapping his leash in the aftermath of the bloodbath; or the ringing in their painfully acute ears of the rat-a-tat of Capone's heartless love song, hand-delivered long ago to an unwilling gathering of wallflowers.

This Valentine's Day, whether you are a lover or a fighter, I hope you receive a kind word--and maybe even a fond embrace--from someone you love. Above all, I hope you stay out of the way of the bullets—in this city that has come tragically ‘round to violence and murder once more.

Ursula Bielski is the author of 12 books on Chicago's haunted and dark history and the founder of Chicago Hauntings Tours, now part of American Ghost Walks. She is the host of “The Hauntings of Chicago” on PBS and the co-host of "The Haunting of M.R. James." The Original Chicago Hauntings Bus Tour and the Lincoln Park Ghost Hunt Tour visit the site of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, the only ghost tours in Chicago that travel to the site.

Relive Chicago's Bloodiest Valentine: The Mob Massacre Tour

Step into the haunting world of 1929 Chicago's most infamous gangland hit: The St. Valentine's Day Massacre. Experience the chilling tale of how Al Capone orchestrated the brutal execution of seven rival mobsters in a Clark Street garage that would forever change America's crime history. Walk the haunted grounds where phantom screams still echo and dogs still react to unseen presences at the massacre site. Whether you're a mob history enthusiast, paranormal investigator, or seeking a dark slice of Chicago's past, our

Chicago Ghost Tour offers an unforgettable journey into the city's most notorious gangland ghost story. Don't miss your chance to visit the infamous site where Chicago's bloodiest Valentine's Day unfolded—if you dare to face Chicago's darkest love letter.

Check out our Chicago ghost tour reviews on Google to see why this tour is a must-experience. Ready to embrace the eerie? Reserve your spot today!

Dive deeper into the mysterious world of hauntings with our curated collection of paranormal investigations and ghostly encounters. Read more stories like this in “Ghosts of Lincoln Park: A Chicago Hauntings Companion” by Ursula Bielski, a book of downtown Chicago ghost stories written by our own American Ghost Walks team. Click here for more.

Dive deeper into the mysterious world of hauntings with our curated collection of paranormal investigations and ghostly encounters. Read more stories like this in “The Original Chicago Hauntings Companion” by Ursula Bielski, a book of Chicago ghost stories written by our own American Ghost Walks team. Click here for more.

Are you fascinated by the supernatural and craving more spine-tingling tales? Whether you're a skeptic seeking evidence or a believer looking for your next supernatural fix; "American Ghost Books" offers everything from historical haunted locations to firsthand accounts of paranormal experiences. Each book has been carefully selected to provide authentic, well-researched stories that will keep you turning pages well into the night. Don't let your curiosity about the supernatural remain unsatisfied – explore our collection and find your next ghostly adventure today!

Find Your Next Paranormal Experience

Lincoln Park Hauntings Ghost Hunt and Ghost Tour

Learn MoreOriginal Chicago Hauntings Ghost Bus Tour

Learn More