"The Massacre Tree"—The Roots of Chicago's Story

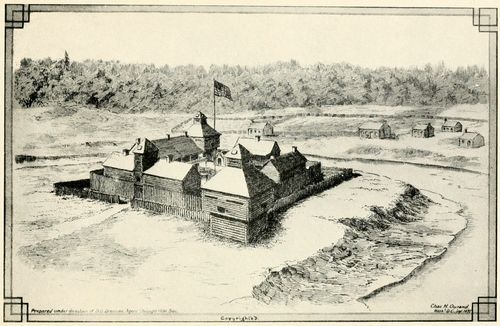

In the summer of 1812, the settlement at Fort Dearborn was young, diverse, and fatally unstable, comprised, in the words of Nelson Algren, of "Yankee and voyageur, the Irish and the Dutch, Indian traders and Indian agents, half breed and quarter breed and no breed at all." By 1800, the competition for hunting areas and trade routes had ruined much of the independence natural to the Great Lakes tribes.

The native element of the emergent pan-Indian culture could not avoid engaging in trade-based subsistence and became largely dependent on trade goods. Their pottery making had become extremely rare by I 780, and the cultivation of maize, once a unifying tribal activity, had devolved into a means of supporting white populations. Soon, the inevitable depletion of wild game forced the Potawatomi to repurchase their own harvests from white traders.

The toppling of the Chicago area's native equilibrium happened in the blink of an eye. Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, a mixed-race fur trader from Santo Domingo, had been the area's first settler, living at the river for 20 years before the tum of the 19th century. During his residence there, the wilderness had remained literally unbroken... as Chicago writer Nelson Algren wrote:

To the east were moving waters as far as the eye could follow. To the west a sea of grass as far as wind might reach.

After living peaceably in a modest home for nearly two decades, DuSable sold his land to a man named John Lalime, who aimed to take up indefinite residence in DuSable's quiet cabin at the mouth of the river. That intention was abruptly halted when John Kinzie arrived in Chicago and seized the property in 1803.

Although the Kinzie title has still not been found, most historians agreed that the house, on the bank of the Chicago River opposite the fort, was the same lot that DuSable sold to Lalime in 1800. Records in Detroit, however, show the sale of that same land to Kinzie by Pierre Menard, who passed the parcel to Kinzie for fifty dollars, claiming to have purchased it from an Indian named Bonhomme.

When Kinzie arrived in Chicago, he assumed the right to the disputed title, at the same time beginning a rivalry with Lalime that would end in the murder of the latter at the hands of his foe.

Yet, only with Kinzie’s whirlwind arrival, less than a decade before the fort's destruction, did the settlement at the river begin to come alive. Preceded by his reputation as a quick-witted Indian trader, Kinzie, a British subject born in Detroit's Grosse Point area, immediately settled his family in the safe shadow of Fort Dearborn.

For nearly ten years, he ruled the realm of settlers and "savages" that together began to suggest civilization, at least when Kinzie himself wasn't sparring with his fellows. For Kinzie was a melding of opportunism and temerity, and when he came to Chicago, aiming to position himself between the portage fur trappers and the Detroit market, he brought along his whole collection of brash personality traits to help him along, using what one critic called” guile, intimidation, and the soporific effects of British rum” to “persuade” Detroit bound trappers to undersell him their pelts.

Kinzie's attitude set the standard for the business relationships that affected every aspect of life at Fort Dearborn. That attitude took its life largely from the shared distaste of men like Kinzie for all others, something that overshadowed any feelings of community.

Still, Kinzie's self-assuredness served to comfort and encourage those who sensed in him a certain quality of leadership. And it was this self-styled security enjoyed by Kinzie and his comrades that left them ill-prepared for the events to come. Eventually, the resentment of the native population became too strong for even a charmer like Kinzie to dismiss.

The inevitable slap of reality came in 1812 when fighting erupted along the northwestern frontier. The fate of more than the fort was sealed when a pair of decisions was delivered. General Hull's order of the evacuation of the fort was quickly followed by Captain Nathan Heald’s own demand that the settlers and soldiers destroy all whiskey and gunpowder—a decision that enraged the Native Americans.

On August 15, 1912, Captain Billy Wells arrived at Fort Dearborn, escorted by friendly Miami Indians from his home of Fort Wayne, Indiana. His plan was to give the hostile Natives at Fort Dearborn everything his band could carry, in hopes that the Indians would allow the Fort Dearborn settlers safe passage across the dunes to Fort Wayne. But while Wells had a plan, he didn’t have a hope: he arrived at the Fort that morning with black paint smeared over his face: a sign he believed his death would come before day’s end.

Predictably, as the grim procession of soldiers and settlers crossed into the open landscape headed toward Indiana, Indian allies of the British beheld them with bitter eyes. When the line reached a smattering of cottonwood saplings near present day 18th Street and Indiana Avenue, a group of Potawatomi pounced.

Of the 148 members of the exodus, 86 men and women and 12 children were brutally scalped and murdered, a wagon of children axed in their skulls (claimed by the Indians to have been an act of mercy because their parents had been killed). Billy Wells fell with the dead, and the Indians promptly cut out his heart and ate it to absorb his immense courage.

Those who survived were taken as prisoners. Some of these died soon after, while others were enslaved and later sold to the British and into freedom.

Appealing to the Potawatomi on the strength of the business relationships that he had forged, Kinzie and his family were spared.

The fort was burned down.

The scalped corpses of victims remained unburied where they fell, splayed across the Lake Michigan dunes or half buried in the loamy soil. When troops began arriving four years later, they were met by a ghastly host of images: the pitiful skeleton of the erstwhile fort; the abandoned Kinzie cabin; the decaying bodies of settlers and soldiers, all returned to the prairie, all victims of the wilderness and of a desperate, undeclared war.

By the time John Kinzie returned to his property a year later, troops erecting the new Fort Dearborn had re-buried many of Kinzie’s neighbors in the new fort’s cemetery. Never looking back, Kinzie sought in vain to climb again to his old seat at the peak of the portage fur trade. When his bitter efforts went unsatisfied, he stooped to employment with the new king, the American Fur Company.

The gruesome events that occurred on the Chicago dunes that summer day in 1812 seem to demand commemoration via haunting legends. Indeed, the site of the fort itself is reported to be well-protected by marching troops of massacred soldiers who stand guard over the phantom fort site, now the south end of the Michigan Avenue bridge. Yet the site of the actual massacre remained placid until many decades later, after the physical formation of the city of Chicago. Only then, during routine roadwork near the site, did workers uncover remains dating to the early 1800s which were probably massacre victims.

Whatever the identity of the remains, after the accidental excavation, apparitions described as "settlers" began to present themselves to passers-by near 18th and Calumet.

For many years, Kinzie himself was left to the quiet of his grave. Lauded by the histories penned by his own kin and taught for years as part of the Chicago public schools’ curriculum, Kinzie became the city's first hero. This entitlement went largely undisputed until historian Joseph Kirkland began to focus a more critical eye on the figure of Kinzie. As the truth unfolded, Chicagoans began to learn more about the city’s mythical founding father. Summing up the new research was the sentiment expressed in Nelson Algren's commentary of early settlement in his classic, Chicago, City on the Make. There, he described the city’s early settlers as simply the first in a long line of hustlers, as those who would do anything under the sun except work for a living, and we remember them reverently … under such subtitles as "Founding Fathers" or "Far-Visioned Conquerors," meaning merely they were out to make a fast buck off whoever was standing nearest.

On visiting John Kinzie’s grave today, one may be stricken by its placement at the outer edges of prestigious Graceland Cemetery, far from the plots of the Pullmans, the Fields, the Palmers, and the architects, artists, writers and inventors who came after him to build Chicago into a world presence. Symbolic of his own ultimate place in Chicago’s history, Kinzie has found himself on the outside, looking in on all he imagined himself to have been courageous, enterprising, visionary and faithful.An outsider he wanted to be, and an outsider he most certainly is.

As for the Massacre victims, exactly where they were buried—or “half buried”—along the sandy lakefront expanse of the time is hard to discern. Some accounts placed the mass grave at the house of Fernando Jones, 1834 S. Prairie. Others thought the burials were done near the Pullman mansion, which stood until its 1922 demolition at 1729 S. Prairie. Most, however, believe that the burials occurred at 18th and Calumet, the site of today’s “Battle” of Fort Dearborn Park, and early maps show a “Massacre Cemetery” at that site.

It is also not entirely certain that all or any of the Massacre victims were re-interred at the Fort Dearborn Cemetery along the river when the complex was rebuilt in 1816. In fact, it is more certain that at least some remain at the ambush site, turned into the soil and built on by the Chicagoans that came after.

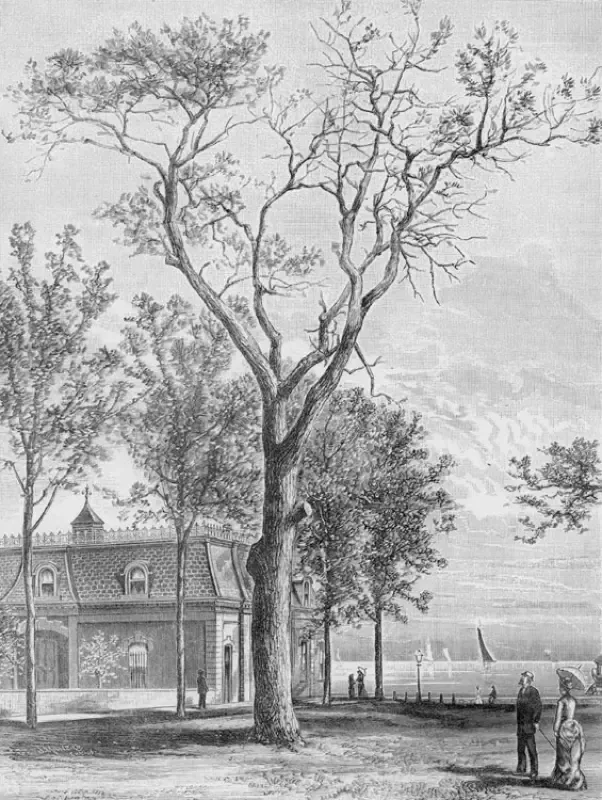

Those who survived the Fort Dearborn Massacre, however, always marked the spot in their memories by that cluster of cottonwood saplings that had sprung up shortly before the fateful day. The tender shoots which witnessed the horror on the dunes that summer mostly died away as the years went on, except for one: a towering specimen which became known as the Massacre Tree. When locals called it an eyesore and petitioned for its removal, old timers asked the Chicago Historical Society to protect it, which they did. When a storm finally killed it, a portion of its felled trunk was reportedly sawed out and given to the Society, where it is said to remain today, stored among its countless curiosities.

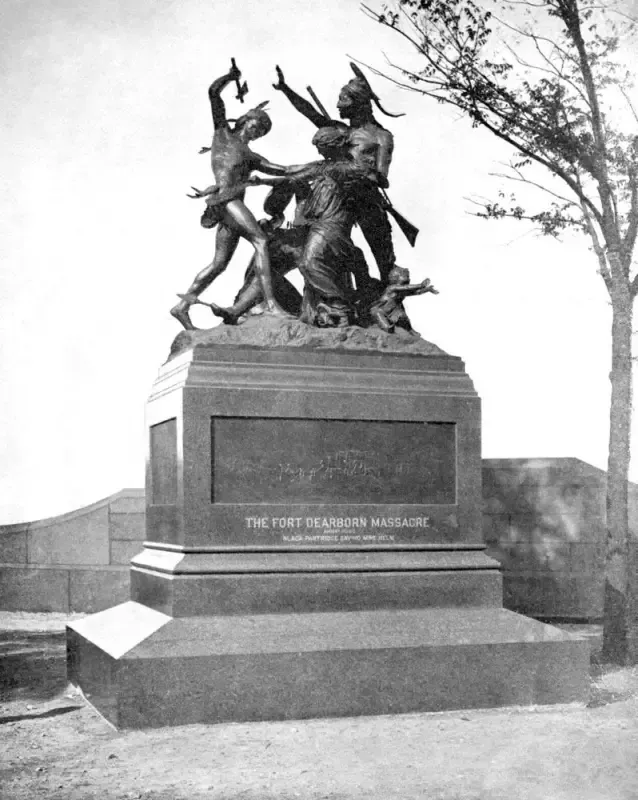

After the loss of the tree, George Pullman commissioned a monument for erection on the site. Carl Roehl-Smith forged the mammoth bronze, entitled “Black Partridge Saving Mrs. Helm,” depicting a scene from the bloody clash of 1812. Legend has it that the commission stemmed at least partly from Pullman’s wish to placate the Massacre victims he believed to haunt his Prairie Avenue home. The monument did not remain long at the site, being removed not long after the demolition of Pullman’s mansion and the deterioration of the elegant Prairie Avenue district. In 1931 it was installed in the lobby of the Chicago Historical Society before disappearing into storage in recent years, the victim of lobbying by the American Indian Center, who called the monument racist. According to accounts, the piece is now in storage in a garage near Roosevelt and Wells. The park replaced it, marked by the bronze plaque remembering the “Battle” of Fort Dearborn.

The site of the Fort Dearborn Massacre is, today, barely distinguishable as the place where, over two centuries ago, an iconic scene played out on the bloodied sands of the fledgling Checagou. A handful of the old mansions still stand along the cobblestoned Prairie Avenue, most of them demolished and rebuilt, ironically, “in the fashion of” the destroyed homes.

Condominium complexes shadow the park below, where Calumet Avenue skirts a row of new, million-dollar townhomes. The Illinois Central tracks run behind it to the city center, where the body of President Lincoln passed through Chicago after his assassination, and beyond that lies Soldier Field and the dark waters of Lake Michigan.

But the wind still whistles off the waves, the sand still blows up from the shore. And ghosts still wander here, both in and out of these new posh digs. Long skirted wraiths of settlers are seen fading around dark corners. Phantom horses are heard galloping down the hall of a Prairie Avenue complex built in 2002.

Footfalls follow behind strollers down these streets. If you listen closely on a summer night as you walk, you can sometimes still hear above the night breeze what sounds like the screams of the Massacre victims and the war cries of Indians.

Further up the lakeshore, at the mouth of the river, phantom soldiers still keep watch where the fort once stood, in the shadow of a bridge relief showing Billy Wells locked in battle with an Indian opponent, his final moments captured in stone.

Meanwhile, at Graceland cemetery, far from the wild shores where his fellow settlers found an earlier, though more honest rest, John Kinzie may now wish for the violent but valiant death he once fled, a death to which some massacre victims may still be calling him... from a little patch of grass at 18th and Calumet, where once stood “The Massacre Tree.”

Dive deeper into the mysterious world of hauntings with our curated collection of paranormal investigations and ghostly encounters. Read more stories like this in

“Ghosts of Lincoln Park: A Chicago Hauntings Companion” by Ursula Bielski, a book of downtown Chicago ghost stories written by our own American Ghost Walks team.

Click here for more.

Dive deeper into the mysterious world of hauntings with our curated collection of paranormal investigations and ghostly encounters. Read more stories like this in

“The Original Chicago Hauntings Companion” by Ursula Bielski, a book of Chicago ghost stories written by our own American Ghost Walks team.

Click here for more.

Are you fascinated by the supernatural and craving more spine-tingling tales? Whether you're a skeptic seeking evidence or a believer looking for your next supernatural fix; "American Ghost Books" offers everything from historical haunted locations to firsthand accounts of paranormal experiences. Each book has been carefully selected to provide authentic, well-researched stories that will keep you turning pages well into the night. Don't let your curiosity about the supernatural remain unsatisfied – explore our collection and find your next ghostly adventure today!